Imagine seeing this in the guidelines of a playwrights’ opportunity:

*If your play is selected, you are responsible for a $100 participation fee. You are also responsible for finding a director, casting the show, supplying sets, figuring out tech and lighting, running rehearsals, and, in all truth, filling seats. Just so you know, it could end up costing you thousands.

Would you submit? Probably not.

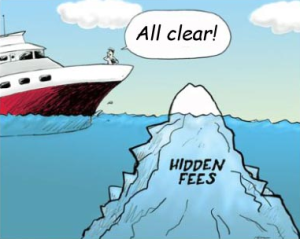

But the fact is that many playwrights do submit to opportunities just like this because the above paragraph is never part of the guidelines. It’s only after playwrights are selected that they hear the fine print and, too often, by then, they’re so excited at having been chosen that they try to make it work, often getting in over their heads in the process. And that’s what these dubious contests (who I suspect accept far more than they turn away) count on. That, and a misguided belief that this will be valuable “exposure.”

It is my feeling that too many of these festivals prey on unsuspecting, hungry, and/or more inexperienced playwrights by promoting the opportunity to have a New York City production—it’s telling that these festivals don’t seem to be quite so prevalent in other regions—without ever mentioning how much it’s going to cost, or the very real possibility that nobody is going to show up. Of course, promotion is an option that might pay off, but that’s going to cost even more.

From what I’ve seen, the bulk of these festivals take place in New York City, which, for a non-resident can mean additional expense, and not just for travel and lodging: one long-time festival charges an additional $900 for out-of-town participants, which is just one example of the hidden costs inherent in many of these operations. Another annual contest that offers prize money (though far less than what it cumulatively collects) requires that the shows that advance be remounted for another round of judging. And if you win? At least you might recoup some of what you’ve spent, the but honor of the prize is as dubious as the festival that awards it. (And speaking from early experience: if it’s a ten-minute DIY festival, it’s even more useless, particularly if prizes awarded by audience favorite.)

But what about the New York City International Fringe Festival (NYCIFF)? Don’t Fringe shows go on to further life? What about URINETOWN? What about DOG SEES GOD? These examples, and the success and competitive nature of the NYCIFF are the models these newer festivals like to point to in supporting their value. And yes, of course, it happens, but when you consider that there are 200 NYCIFF shows every summer, it happens more infrequently than Fringe hopefuls would like to believe. And that’s even considering that the New York Fringe curates its shows carefully, accepting only about 20 percent of the 1000+ applicants. And that FringeNYC is an established twenty-year old festival with cred, promotion, and lots of reviews, including, often, the coveted New York Times (and still I know plenty of people who had Fringe shows reviewed by the Times and didn’t get another production). And that many acts who present at the NYCIFF hire expensive casting directors, publicists, and managers to help their shows stand out in a crowd.

URINETOWN is an oft-cited fringe success story–but it’s a rarity.

In other words, even though the New York Fringe is probably your best shot (for one-acts, the OOB Samuel French Festival is the best equivalent) at getting your work seen with this type of model, the odds are still incredibly long.

None of this is to say that you should not self-produce, but, if you choose to, you need to know exactly why you’re doing it, and choose the method by which you do it accordingly.

*Is it to learn all facets of the business? If so, you can probably do it a hell of a lot cheaper in your own city, or even at a Fringe festival in a smaller city. I often promote the Buffalo Infringement Festival, which turns away nobody, is free, gives you a venue and simple tech, and promotes your show. If your goal is learning—about either the process or your play—there are cheaper options than putting up a New York City show that nobody will see and, quite frankly, if you produce in your hometown, at least you have friends and family who will come.

*Is it just to have your work seen, finally? See above.

*Is it to get your work noticed, build a life for it, get an agent? This is the dream, but it’s also the loooooong shot. As such, your goal shouldn’t be one of these smaller, unknown festivals, but a bona fide production at a New York rental facility that has good cred, regular reviews, and a name for itself, like 59E59 or the Theatre Row venues (commenters, please feel free to jump in with other suggestions). You’ll still have to pay for publicity and all the other stuff, but your show will be taken more seriously, which gives it a better chance of being “noticed.” There are people who do this successfully; find them, talk to them. There is a lot to be learned that goes before and after just putting up the show.

So how can you avoid these festivals seemingly do more for the promoter than the playwright? Watch for language in the opp that says things like:

*We will supply x hours of rehearsal time.

*You will get x hours of tech time.

*The festival provides a theater, scenery, etc.

*This is an opportunity for playwrights to see their work on its feet.

*Show must have directors attached.

*Show will be given x number of performances.

*Talk about “presenting” your work rather than having it produced.

*Any use of the word “participate.”

*Any indication that you are responsible for filling seats (and mention of charges in relation to this).

*Too big a deal being made about no fee to submit or apply (often with an asterisk next to it).

None of these are set in stone but many are flags that this is a DIY opportunity, and warrant an email to ask for 1) clarification and, especially 2) information about any charges associated with acceptance to this opportunity.

Even with knowledge of the aforementioned language, it’s sometimes easy to submit to something without being aware (I’ve done it) because the language in a good number of these opps is vague—I suspect to lure playwrights in in the hopes that once accepted, they’ll be too excited to question. If you’re accepted to a DIY Festival—either by design or accident—if you haven’t heard of it, or it’s brand new (and there are new ones popping up every month, it seems), then it should be subject to your inquiry, research, and vetting. What are the hidden costs? How are prizewinners chosen? What are your responsibilities? Find others who have been involved, and solicit some honest feedback. And always remember that being selected in and of itself does not obligate you to anything; it’s not too late to ask questions or, as I’ve done when I’ve made the mistake, let them know that you’re unavailable to self-produce.

Finally, before I get flamed from here to California by someone who had a wonderful experience that led to something else wonderful, there are, of course, always exceptions (Downtown Urban Arts Festival, for example, offers a production stipend; I’d love to see others detailed in the comments as well). But with more and more of this variety of “opportunity” popping up, it’s on us to weigh the monumental odds against our own wherewithal, financial circumstances, and perceived gain. My only goal in this post is to raise awareness, let playwrights know that the benefits of self-production don’t have to be learned in New York City, there are other options and, that if and when you want that NYC production and are ready to spend the money to do so, it’s worth fully researching options that will give you what you want.

That’s all. No flames.

Please follow me on Twitter @donnahoke or like me on Facebook at Donna Hoke, Playwright.

Playwrights, remember to explore the Real Inspiration For Playwrights Project, a 52-post series of wonderful advice from Literary Managers and Artistic Directors on getting your plays produced. Click RIPP at the upper right.

To read entries in Playwrights Living Outside New York series, click here or #PLONY in the category listing at upper right.

I wholeheartedly agree. I participate in one of these festivals and I learned a lot but I’m not sure that I would do it again.

Sure you get the opportunity for several performances but the reality is some if not most are throw-a-ways. Friday at 5pm in July? Your possible audience is either at the beach or still at work.

Right–that’s something else you’re often not told. :/

Hey Donna,

I’m enjoying your blog very much. I wonder if the DG has anything in mind in terms of checks and balances to make life better for playwrights.

I recently had an email conversation with a fellow who had no real explanation for why his advertisement said one thing, but his submission form said something else.

I’m copying the exchange because I think it’s worth noting the rationale the fellow uses to justify the hidden money.

==

Me:

“I have one question.

On the NYCPlaywrights post it is states:

Flying Solo is a festival of solo shows that doesn’t charge participation or submissions fees. That’s right – NO FEE – Cheaper and better than the rest. Seriously.

Plus we provide a tech/lighting designer/Board op for your run! [however if your show is complicated you may wish to bring your own tech person]

On the application form there is an item which reads:

I agree to pay a $50 tech fee if selected for Flying Solo 4

Can you please explain the discrepancy?”

Reply:

“Hi Jason,

The fee is to cover the cost of running the lights, sound, and person to operate them. It is not a Submission fee, but a tech fee as it states.

Best, ______”

Me:

“Thank you for the reply.

The original post makes no mention of any fees. It says all is provided, including dedicated personnel, fee-free.

If you do have fees of any kind associated with your show, may I suggest that you include that information up front and not only on the application.

Plus, if I provide my own tech person, then what is the $50 going towards?”

Reply:

“Dear Mr. Lasky,

The $50 goes towards the Operational cost of the theatre. Other festivals charge upwards of $500 just to participate. We feel that our $50 fee is quite generous on our part. If you feel differently you do not have to apply, though we will be disappointed we fully understand your concern.

Best, __________”

Me:

“Hello again,

Then why don’t you advertise that there is a $50 Operational cost on your website and on all websites carrying your submission opportunity? This is money that comes out of the playwright/producer/performer’s pocket that must be paid in order for him/her/them to participate. Like a fee.

If you want the sum and substance of your whole festival to help pay rent, then be transparent about it like those other festivals that you mentioned.

And if no one else has made an issue of this, then I’m happy to be the first.

Thank you, and all the best.”

End…

– Jason

Hi Jason — Thanks for sharing this exchange, which is typical. These festivals often get defensive about how they’re better than this one or that one. I think it’s worth asking what the festival promoter is getting out of running a festival? They like to say “we want to help playwrights,” but such a run on altruism seems unlikely.

The Dramatists Guild is currently at work on creating Best Practices Festival Guidelines. Stay tuned.

Your blog is chock-full of insight, as usual, Donna. To me, this all boils down to a matter of validation of my talent as a playwright. I can either buy that validation by paying whatever it takes to put my work before the public, or I can earn that validation simply by writing compelling plays and hoping others will find them irresistible. I know too many playwrights who, after seeing their scripts rejected repeatedly by theaters, festivals, contests, etc., declare, “They’re all nuts! I’ll show them! I’ll do it myself, damn it!” That’s self-deluding. They never consider that the fault might lie in the script and not in the system they’re railing against. As a specialist in short plays, I’ll pay a submission fee on occasion if the fee is low enough and submission is via e-mail and I think the odds are in my favor – after all, it stands to reason that fees lessen competition — but I resolved to pay nothing else soon after I began writing plays four years ago. Then, when a theater, festival or contest accepts one of my short plays, which is happening more and more, I can bask in the glow that somebody out there likes my work enough to want to showcase it with no strings attached. Sure, even that system may be rigged on occasion, but at least I’m not doing the rigging. What I’m doing is honest. That glow is real.

Great post.

If producing a show on your own is expensive, consider collaborating with local playwrights and share the cost. You can each wtite a 10-minute play on a theme or fit together pieces already written.

This is great! Keep the suggestions coming!

Also, outside-NYC folks may not realize the downside of a “New York City Production!!!” – which is that on any given day in New York there are at least a few hundred theatrical performances happening, and chances are your festival will be fairly-to-comically low in visibility, and in the pecking order of the NYC theater-going audience’s priorities (and often, too, may be performed at inconvenient or non-standard times). You’d be surprised, in a city of 8.3 million, how few people can show up for something. Plus, although the city undoubtedly has the deepest talent pool of actors anywhere, those who participate in your festival may prove to be surprisingly disappointing. I live here and I almost never apply to anything that’s going to cost me money to put on — and if I do spend anything, I make sure I hand-pick everyone involved.

I’m not a big fan of DIY festivals (although I did do the United Solo Festival, but a one person show is a different animal) but I think one of the reasons they seem so egregious, especially to those of us that have primarily lived outside New York, is that there’s a very basic world-view disconnect. New York City is really the only place where the most prominent theatre (Broadway and Off-Broadway) are essentially for profit ventures. They have investors, they rent venues, etc. So the DIY is kind of a smaller version of a standard NY theatrical business model. But in the rest of the country, we have regional theatres, LORT theatres, community theatres, store front theatres, etc. which are primarily 501C3 not-for-profits. That means all the money comes not from individuals putting up money, but from fundraising campaigns, foundation grants and government grants. There is an existing infrastructure supported by these funds that then selects which plays to produce. In New York, a lot of times, the infrastructure is created purely to produce and market a specific show. So these DIY festivals fall somewhere in between these two things.

Amendment: I did just look up the ratio of commercial to non-profit off-broadway houses. It looks like it’s about 50/50. For every Soho Playhouse, there’s a Playwrights Horizons. I assume it’s similar for Broadway houses as well. Nevertheless, commercial theatre is just something we don’t see much of outside NY, unless it’s a presenting house booking theatrical tours.

This makes a lot of sense, David, and certainly explains why so many of these festival coordinators are taken aback by our responses to their “opportunities.” The way I see it, it makes it even MORE important for playwrights to understand exactly what they’re getting into, and what if any benefit can be derived from their participation. While Broadway et al are for-profit models, there’s a lot more infrastructure going into those ventures, which gives them a much greater chance of visibility and success than these production are ever going to get, and I’m not sure that all the playwrights who enter and get chosen for these things understand that–especially because, as you point out, that’s not a model we’re used to outside New York City.

KC Fringe is its own state of affairs. A decade ago it started and the state of local playwriting (and local theater) was set. Kansas City’s unique inferiority complex about its own community meant that local playwrights were not being produced, not locally at least. Fringe festival opened up a floodgate of opportunity for local talent and ten years down the road, surprise, surprise, local professional theater companies are producing plays. Ignore that they had to be battered over the head for a decade, but progress is progress.

That said, with a few exceptions, KC Fringe is a terrible venue for out of town playwrights. Our audiences have come to accept it as our playground and the non-KC events tend to be less well attended.

I’ve never lost money self producing here. I’ve never made serious money either. But I’ve been able to develop my plays in front of a paying audience. Which is the point.

Roy Proctor Your blog is chock-full of insight, as usual, Donna. To me, this all boils down to a matter of validation of my talent as a playwright. I can either buy that validation by paying whatever it takes to put my work before the public, or I can earn that validation simply by writing compelling plays and hoping others will find them irresistible. I know too many playwrights who, after seeing their scripts rejected repeatedly by theaters, festivals, contests, etc., declare, “They’re all nuts! I’ll show them! I’ll do it myself, damn it!” That’s self-deluding. They never consider that the fault might lie in the script and not in the system they’re railing against. As a specialist in short plays, I’ll pay a submission fee on occasion if the fee is low enough and submission is via e-mail and I think the odds are in my favor – after all, it stands to reason that fees lessen competition — but I resolved to pay nothing else soon after I began writing plays four years ago. Then, when a theater, festival or contest accepts one of my short plays, which is happening more and more, I can bask in the glow that somebody out there likes my work enough to want to showcase it with no strings attached. Sure, even that system may be rigged on occasion, but at least I’m not doing the rigging. What I’m doing is honest. That glow is real.

Hi Donna,

I wonder if you or any of your readers have feedback they’d like to share about the Thespis Theater Festival (NYC).

Cheers,

Casey

Sometimes we are so hungry for a production we will do almost anything to see our script on it’s feet. Unfortunately, there are those who are aware of that and are more than willing to take advantage. Apart from the workshop potential, I don’t see the value in paying for a production or self producing. If looking to build a reputation, it’s much better to work your ass off to build a production history of theatres that paid to produce your work meaning they loved the script, not because they loved your cash.