I read a lot of ten-minute plays. Not only do I co-curate BUA Takes 10: GLBT Short Stories, but I run TRADE A PLAY TUESDAY and often participate myself (contrary to some beliefs, I do NOT read every play that comes in, only if I’m trading myself), as well as read for several other festivals and contests. It’s fair to say I read and/or see hundreds of ten-minute plays a year. I’ve also written nearly three dozen that have had productions around the world. As such, and even though there are great books out there on the ten-minute play (Gary Garrison’s A More Perfect Ten, for starters), I’m going to list what I feel (and as always, your mileage may vary) are the most common problems, the ones that generally preclude a play getting chosen for our festival or me recommending a play for another, and the things I find myself commenting on most often when others ask me for feedback. (And as a thorough disclaimer, these are clearly MY opinions only; I have seen any and all of these types of plays chosen and presented in festivals, but, I have to admit, I’m never sure why.)

1) It takes too long to get going. In a ten-minute play, audiences should know or at least suspect what the conflict is by page two. Very often, there is a lot of introductory and lead-up dialogue before the story actually starts on page four or five. This means it’s actually a five-minute play with a bunch of filler up front. Four or five pages in a ten-minute play is too much to waste.

2) The characters are mouthpieces. The play has a message it wants to impart, but rather than putting characters in a dramatic situation to impart it, the characters (usually two) are plopped in some neutral locale, where the intended subject randomly comes up, and they discuss the two sides of the message point by point (or close enough). It doesn’t matter who wins or loses the argument, nobody leaves the argument changed, and the result feels like heavy-handed preaching. It’s conflict without stakes.

3) The play goes nowhere. Writing dialogue can be really fun, especially when the characters take over and say things we never expected them to say. But when they’re done having free rein, it’s important to go back over what they said and make sure there are sound reasons for keeping it. Does the dialogue move the story forward and drive toward the ending? Does it contribute to the theme? Does it reveal their wants? If that information were not in the play, would it make a difference? Despite clever dialogue, do the characters end in the same place they began? Even ten-minute plays should show a journey for someone. (Facebook commenter Tom Rushen adds that this is often a problem when the “play” is an excerpt from a larger piece, and has no impact out of context.)

4) The play is much longer than ten minutes. Dense dialogue means the play is going to be more than a minute a page. Don’t guess; read it out loud. Not all festivals are super strict about length, but if they’re asking for ten minutes, better safe than sorry.

5) The play is an elaborate set-up for the punchline. Some ten-minute plays read as though the ending was thought of first, and the entire play was written to support that punchline. This isn’t to say the ending is bad, just that it needs a solid structure to support and make it earned and satisfying. Very often, with plays like this, the ending is telegraphed because it seems as if it’s the only point to the play. Alternatively,

6) The play is a one-trick pony. There’s a device, say a daughter is coming out as straight to her lesbian parents, and they are disappointed. Instead of focusing on the discourse that might come out of that, and the acceptance journey or something else dramatic, the play is focused on all the reversals that come out of that reveal, at the expense of the characters, the plot, and the play itself. Even if it’s funny, the joke is usually exhausted long before the ten minutes is up, which is why sketches tend toward brevity and often peter out without resolving the conflict in any meaningful way.

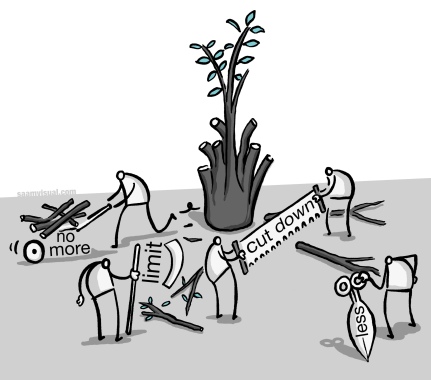

7) The play tries to do too much. One of the beautiful things about writing ten-minute plays is that there is only room for one storyline. That doesn’t mean there can’t be subtlety and beautiful layers to that story, but in trying to incorporate too many themes, the ten-minute play becomes unfocused and confusing. With a solid throughline, supporting ideas may manifest, but there isn’t room for them to be a story unto themselves.

8) There’s not an original idea in it. Some plays are perfectly fine as written, but the whole thing just feels too familiar, the characters too cliche. I’d offer examples but I don’t want to call out something specific that somebody might take personally. A short time ago, I posted on Official Playwrights of Facebook asking if ten-minute plays time out, i.e. do they become less appealing for some reason? I think this may actually be part of it. When I wrote a short play about people being obsessed with technology, it got produced about 15 times in one year; nobody chooses it now. I’m guessing there are how a ton of those out there; maybe you’ve written one yourself. So if something “new” like that can get overdone, imagine how many times readers see things about ordinary situations. If you’re choosing to write about something ordinary, ask yourself “What is going to make this one different from all the others like it?”

Please follow me on Twitter @donnahoke or like me on Facebook at Donna Hoke, Playwright.

Yes. I think some people think of ten-minute plays as skits. That’s where you get problems 5 and 6.

Donna,

I’m sure I’ve hit all the points at some time or another. I’m mostly better but if anything, I’m guilty of point 5 – the punchline. Occasionally 6 – the one trick pony.

Everything you said is spot on and almost works like a checklist of what not to do. So, write a play, compare to checklist. “Yes” to any of them? Start over. 🙂

Well, I would start over.

Good insight, Donna, and a great reminder.

Thanks, Earl! And thanks for being a TAPT regular!

This was great! Everyone who writes 10-minute plays should read this. Very insightful and a nice reminder for me as I’m finishing up a new 10 min. play.

Thanks, Laurie! Feel free to share 🙂

Very well put, Donna!

Great article, Donna. I, too, read a fair number of ten minute pieces and have seen them in festivals, and the play that goes nowhere (just stops at page 10 or 11) is my pet peeve..

Nice observations, here. I’m guilty of all the above. I believe everyone should read their page 1, see where there characters start, and then read their last page, to make sure the characters are someplace else. If there’s no journey, rewrite.

This is great information! Thanks. I plan to go over my current and past plays to check for these things.

Well done. Another suggestion is to think of the 10-minute play the same as a full-length play. 2 pages for the first act (the setup – get everyone interested); 6 pages for the second (conflict/twist at the end); 2 pages for third (coming out on the other end with a solution, question, or dilemma solved leaving the audience with something to talk about)

Thanks you for the info. I have a ten minutes play I would like to submit.

Thanks, Lillian. Good luck with your submissions!

Haha – same wavelength, indeed! Love it – thanks for sharing 🙂

Excellent advice, Donna! We have produced over 400 short, ten minute plays and read thousands. We often see many of the problems you mention.

This is a fine checklist, Donna. I would add one other fault: the play is not about anything, at least anything serious. Whether the two people on a first date hit it off is not enough. I also really like Stanley Brown’s advice to read the first page and the last page to see if the characters have changed. Your observation (#5)about plays that seem all about getting to the punchline mirrors the sagacious complaint about a lot of short contemporary poems: the poet imagines a cool image, makes that the last line or last two lines, and then tosses off a few lines whose only apparent purpose is to get to that last line.

That would be #3: The play goes nowhere.

I would add a variation on #5: writing to the punchline. Or maybe it is a combination of #1 and #5 that I call writing to the inciting incident. Usually one character in the play has news to tell the others, but encounters obstacles that keep that character from telling. In the final moment, the big reveal comes: “I’m Gay,” or “I’m Pregnant,” or “I lost the house in a Poker Game.” or some other revelation that will mean changes for everyone. And rather than deal with the consequences of the reveal, the play ends abruptly, as if the reveal is an ending, or a punchline (when it might actually be the beginning of a bigger play).

That was/is very good information Donna. Thanks for sharing as I’m always looking to better myself and my works.

6 and 7 seem a bit conflicting. Please explain more thoroughly your “layers” with regard to the the elements mentioned. Thank you I will keep a copy of your valuable information.

Being a one-trick pony means you keep going over and over the same idea in your play without exploring it any deeper or coming to any new understanding; the dialogue around this idea is circular and repetitive, making the same points and jokes in different ways, as in the example I gave of a straight girl coming out to her lesbian parents (this one can and often does go hand-in-hand with writing to the punchline). In that same example, doing too much might mean the play now starts to include surrogacy, transgender issues, same sex marriage laws, etc–a kitchen sink of a play that never says much of anything.

I’m new to the group and have not heard of the ten minute play. I’d like to try writing one. Maybe a ten minute play about fifteen minutes of fame! It could work.