Navigating the Divide Between Novels and Plays

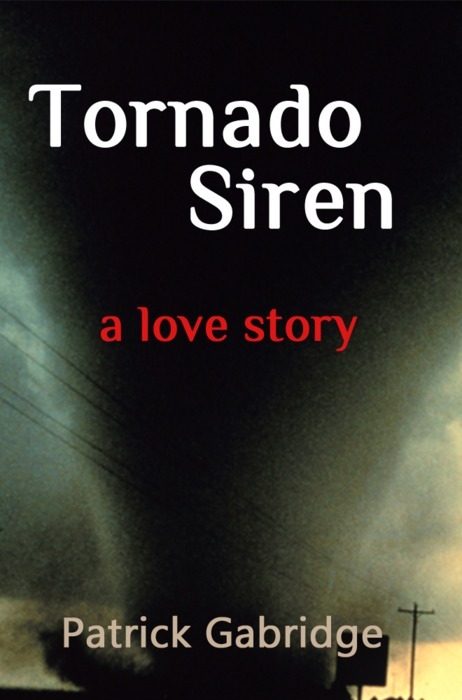

A Q&A with writer Patrick Gabridge, whose novel, Tornado Siren, just became available as an ebook

Patrick is a fellow playwright and founder of the Playwrights Binge that I wrote about last week. Fittingly, I get to feature him here on the final day of the Binge. Thanks to him, I submitted to 58 different venues throughout September. I hope some of you were inspired to submit some of your plays as well. Since I don’t write novels, I wanted to ask Patrick about the process from a playwright’s perspective. I hope you find Patrick’s answers as interesting as I did.

Donna Hoke: I have enormous difficult writing prose. How do you switch back and forth between writing novels and plays?

Patrick Gabridge: I was nervous about writing prose fiction when I started Tornado Siren, which is part of the reason I chose to go with a first person narrative. By telling the story in the first person, from Victoria’s point of view, I could use my playwriting skills, and just think of the novel as an extended monologue. It lent it a much more conversational style that I knew I could write, rather than something more painterly.

For my second novel, I went with a double first-person narrative. My third and fourth are in the third person. By that point I had enough practice to accept the fact that I could actually write a novel.

I don’t find it hard to switch back to writing plays after working on a novel—playwriting is such a natural form for me. I’m always eager to get back to writing dialogue. Switching to prose after writing scripts takes me a bit longer, but I try to be patient with myself and not judge the writing as it comes out. I’m not a brilliant first draft writer—it takes a lot of revision to make the prose something worth reading.

DH: How can you tell whether something should be a play or a novel?

PG: It depends on the scope of the story and on the level of interaction between characters. Tornado Siren was actually going to start out as a screenplay, but I decided a novel would let me develop the characters more, and I wanted to play with descriptive language about storms and the prairie. I had someone ask if I ever thought about doing it as a play, but I think it’s hard to capture the feel of the plains and the storms on stage.

Plays are great for when characters spend a lot of time with each other. In theater, you need to experience people interacting on stage. It’s hard to write an effective play about people who are isolated from each other, physically. In my second novel about a couple of compulsive movers, the story centers on a married couple in crisis, where the husband disappears on an odd journey on a moving truck for a few weeks. It has large geographical scope, and a lot of internal wondering and wandering. It doesn’t lend itself naturally to the stage, but works great as a book.

I’m interested in novelists like Nick Hornby, who write with large amounts of dialogue. In some ways, his books aren’t that different from reading a long, somewhat dense play. He was someone I read a lot when I’m working on a novel—I feel like he’s a kindred spirit (except that he’s English, much better read, and funnier).

Whether I’m writing or reading, I prefer both books and plays where something happens.

DH: Do playwrights make good novelists and vice versa?

PG: It’s probably easier for a playwright to write a passable novel, because the playwright already has an excellent facility for scene, character, and story. As I mentioned with Nick Hornby, I’m not sure writing excellent description is a requirement for a decent novel. I think you could take some of Roddy Doyle’s novels and write them in play format, and you wouldn’t have to change much. Last Orders by Graham Swift is pretty much a big collection of monologues. You could hear each character telling their bit of the story out loud.

I’m not sure most playwrights would make brilliant novelists, because our language skills aren’t exactly the same, and it takes a lot of practice to write genius prose.

I think it’d be hard for a really good novelist to write excellent plays. (You can see that I still primarily identify as a playwright.) It’s a form of storytelling with a different rhythm and less room for messing about. It helps to have a strong understanding of various aspects of theater and to spend a lot time in rehearsal and stage spaces. It takes a while to get that skill. And it’s oddly harder to fake it.

That said, there are people who do it all. Michael Frayn is the first example that comes to mind. Adam Rapp has had quite a career as a playwright, and also has written some highly successful young adult novels. Maybe I can be Adam Rapp when I grow up.

DH: Do you prefer writing novels or plays? (Or screenplays or radio plays?)

PG: I like them all. Writing a novel is a lot more work, partly because there are just so many darn words. I’m working on a Civil War historical novel right now, and the first draft is 120,000 words, or about 400 pages. My newest full-length play, Flight, is about 14,000 words long. I don’t know if it’s ten times more work to write a novel than a full-length play, but it’s not too far off.

The process of taking a play from idea to full production in front of an audience is tremendous fun. I love working with all the people involved—actors, producers, directors, designers. On the other hand, a novel offers a more intimate and intense interaction with the audience—it’s just me and the reader. No set designer or brilliant lead actor to hide the weak spots. I like the challenge of it. Screenplays are fun to write, because I get to watch a movie that no one has ever seen before. And there’s a real challenge within the parameters that exist with a feature-length screenplays. But the process of actually making a movie isn’t as fulfilling as the rehearsal and production process of a play. For me, writing all three is what it takes to make me feel most artistically satisfied.

Patrick Gabridge is a playwright, who has written many plays, including Blinders, Reading the Mind of God, Fire on Earth, and Flight, which have been staged in theaters across the world. His first novel, Tornado Siren, was published by Behler Publications in 2006, and is now available as an ebook. He founded Boston’s Rhombus playwrights’ group, the Chameleon Stage theater company in Denver, the publication Market InSight… for Playwrights, and the on-line Playwrights’ Submission Binge. His plays are published by Playscripts, Brooklyn Publishers, Heuer, Smith & Kraus, Original Works Publishers, YouthPlays, and have been read and used by thousands of actors and students in performance and competition. Patrick is a member of the Dramatists Guild and a board member of Boston’s StageSource. He is currently a Playwriting Fellow with the Huntington Theatre Company in Boston. His most recent collection of short plays,Collected Obsessions, has just been published by Heuer Publishers and Brooklyn.