I’ve never met Larissa FastHorse in person, but, somehow, as these things go, we became Facebook friends a few years back. I loved her posts, which were often about the ups and downs of this life, the insecurities and the successes. But one day, she commented on a mutual friend’s thread about how much she had to travel to maintain her career, and I thought, “That’s #PLONY fodder!” And thus, even though I’ve technically finished this series, Larissa becomes the twelfth entry. Like all #PLONY I’ve profiled, her path to success is atypical, which again proves that #PLONY are a different breed.

What is your geographical history?

I grew up in South Dakota, through high school, and then I was in ballet school, but I did live in Salt Lake City and Atlanta for a while as a dancer, and I moved to LA, where I met my husband; we’ve been in Santa Monica ever since. I didn’t get into theater until my mid-thirties.

Where did you go to school? For what?

I didn’t. I’m entirely self-taught as a writer. I have almost a year of college all put together.

What is your journey to playwriting? You kind of came in backwards, through television?

When I ended my ballet career—I did it for ten years professionally, but I eventually had injuries—because I was in LA, I tried acting, but I didn’t really love that. I’d always written, but I started script writing as an actor when I couldn’t be bothered to find a scene or monologue, and I’d have to make up a name of what it was. I realized it went well, and it was fun, and something I could do. That’s when the idea first came to me.

What had you written before?

When I was younger, I always carried a pen and paper with me. I was never organized enough to have a diary or journal; I just wrote things that could kind of be whatever. I’m an avid letter writer. I like always writing things down, a line or an observation or a moment. I was a dancer, and I didn’t care about doing anything else. Ballet takes up your entire life. That’s the demand of that particular field; you have to give everything to it, so I did.

What do you do with an idea like “be a writer” if you don’t go to school for it?

I spent three years with Career Transition for Dancers getting career counseling. Because I was in LA, I transitioned to film and television to become a writer. I had mentors through my work, really good mentors who said, “Here’s what you need to do.” I wrote for TV first, but I never quite fit in that world. It was always just a little not right. But I got into the Sundance feature film program, I sold two TV shows, and through all that, Peter Brosius of Children’s Theatre Company in Minneapolis found me and commissioned my first play. They asked for Native American writers specifically; they’d read my film script, and it was my writer’s voice they were interested in. They said, “If you can do this, you can do theater.” And as soon as I walked into their theater, I knew I was home. I’ve been addicted to playwriting ever since.

What clicked?

Actors are just dancers with furniture. As someone who came from the dance world, it just felt familiar. The rooms are familiar, the people are familiar. Theater people finally felt like my people, where film and TV never did. The resulting play, AVERAGE FAMILY, was a wide-open commission, though they did hope for something with Native American characters because they’d never commissioned a Native American playwright and hoped to have more representation on their stage.

That was an auspicious beginning!

It’s like the best and worst way to start. They’re a LORT A theater; I had no idea what that meant at the time. I was like, “Great, I grew up in South Dakota, so I’ve been to Children’s Theater Company.” I didn’t realize what their position was in the greater theater world, but, fortunately, coming from television, I was prepared to be a playwright who works a lot on commission, because that’s what you do in TV: you write for a specific audience and actors and production company. There are a lot of requirements and deadlines are really important. That set me up to be a strong commission writer for theater. Before AVERAGE FAMILY opened, I had three more commissions.

AVERAGE FAMILY at Children’s Theatre Company

That’s amazing. A career is born.

One of them I met here in Los Angeles, and wondered how they had heard my name. The sad thing, at that time, ten years ago, is that having a Native American playwright commissioned by a LORT A theater was massive news within our theater community. It’s becoming slightly more common, but still pretty rare. That was news in the theater world and the Native American world, and got my name out there quickly without me having to do much because it was an anomaly.

But you do deliver on those commissions.

Yes. I’ve never taken playwriting classes, but I’ve been told that playwrights aren’t trained on how to work with commissions on how to take feedback and meet deadlines and create something that fits for a specific audience, and that’s something I know how to do. When I do a commission for a theater, it tends to be a perfect fit, and the majority of my commissions get produced.

How many have you done?

Thirteen commissions, and two to three plays on my own. The thing I really struggle with is second productions. A big part of that is I do write specific to a community, and include Native American characters in a lot of my plays so casting is an endless issue perceived by theaters; if they see even one half Native American character, they say, “We can’t cast that.” But when a company puts money into a commission process, they will put money into casting. When they haven’t invested in a commission, it’s a lot harder for them to put money into casting, or hire non-indigenous talent, which I’m okay with, but they’re nervous of that.

How long have you been writing plays? Do you make a living at it?

I’ve been writing going on eleven years. The past eight I’ve been full-time. I only work in theater, no day jobs. Mind you, the living I’m making is around the federal poverty line, but I’m happy about it. I’m thrilled and could not feel more blessed to get to just do what I love.

I entered theater not knowing one person. I didn’t know one dramaturg, one playwright, one artistic director. It was very difficult; I’m realizing now how difficult, because I talk to people and they constantly say, “I went to grad school with this director or actor or whatever…” I knew zero people so I had to make connections on my own without living in New York. It’s been hard work to get to know people and get my name out there.

After that first commission, did you stick with TYA for a while?

Yes, I love family theater, and still love writing for it. I wrote multi-generational theater, and those were my first several commissions. It took a little while to broaden my range, and be seen as someone who can write for both adults and family. And it was never like I wanted to quit family theater—I don’t at all—it was a slow realization that I can write other things. I started getting workshops with other pieces, and that slowly broadened. I think the first production was CHEROKEE FAMILY REUNION, which was a commercial piece for a tourist market in North Carolina in a 2,800-seat amphitheater. Although it was still for a multi-generational audience, it wasn’t considered family theater.

In your nontraditional path to playwriting, how did you educate yourself?

I’m fortunate that this is what I do all the time, but I still constantly feel like everybody’s got some secret that I don’t know because I’ve never to school or taken a playwriting class. I always feel like everyone’s got some secret that I don’t have. That they have some secret tool that tells them how to fix it, but that’s probably just my own insecurity, because now that I talk to playwrights, no one really knows.

I had a lot of mentors, I do well with mentorships. Once I got into theater, I had several mentors, a lot of different folks that said, “Here’s what you need to do, here’s the things you need to go to, the plays you need to be reading,” and pushed me to create my own education. I still work at my own education constantly, which might be a slight difference from people who went to school. They might say, ‘Now I’m done,’ and I’ve never had that feeling. I’m constantly researching old ways of working, finding new ways of working, never ending my education.

I read endlessly. I don’t read books about writing. I tried to read one once but it was so negative: “Writing is horrible, you’ll never be able to make a living.” Why would you read this? I don’t need this in my brain. I don’t see how putting those negative thoughts into your head is going to help you be successful. That’s the only time I ever read a book on playwriting and I gave up in the first chapter. I read plays, and different forms of storytelling; I’m a junkie about how different cultures tell their stories. Any time I go to anything, I study the audience and how they interact with each other, the space, the presentation. I’m constantly studying how people work together and create entertainment. That’s probably my biggest inspiration—audiences and groups of people.

When/how did you get an agent?

It wasn’t right away. I worked with an entertainment attorney who was amazing, worked on commission, and took me on to do all my early contracts. Because of him, I could do submissions that were “agent only.” Eventually, after I won the NEA Distinguished New Play Development Grant in 2010, a friend of mine said, ‘You should use that to get an agent.’ I had a second commission at Children’s Theatre Company so I contacted every dramaturg I knew and asked them to recommend me. I spent my own money, went to New York, did agent interviews, and ended up with the one I was absolutely not interested in, which was Jonathan Mills at Paradigm. I wanted nothing to do with a big agency. I worked with them in film and TV and didn’t like it, but he blew me away, just said all the right things. He cared about the career I wanted. Every other interview started the meeting with limitations. “Because you’re a Native American female, you can’t do this. Because you live in LA, you can’t do this.” Just limitation after limitation, but Jonathan came in with possibilities: “What is your dream and how can I get you there?” In May, he flew out to see my play in Kansas City with me because he’s that kind of agent.

What limitations do you find in being a #PLONY? Benefits?

It’s hard. I talk to New York artists who have never had to work outside of New York, and that’s incredible. There’s such a concentration of paid work that they can stay and have a life and a career. That is not possible where I live in LA. We have tons of amazing theater, but not much that can pay enough to live on. The only way I can make this happen is to travel six months out of every year. I spend half of my life at home and half on the road, and that’s the only way I can do this and survive. I have an amazing partner who is also in the arts and understands, and we make it work. We don’t want kids anyway, but there’s no way; I’d have to quit what I do to have children.

What do you do all that time on the road?

Workshops, plays, conferences, and productions. I work in collaboration with my directors so I’m in rehearsal with them. That’s the way I worked at my first Children’s Theatre Company play and the way I’ve always worked. It’s a lot of time spent developing plays and getting plays on their feet. I couldn’t make a living as a playwright unless I could spend six months a year traveling. Maybe someday I’ll have higher level commissions where I don’t have to take every job, but, right now, I do. That’s just how I was introduced to playwriting, through a completely collaborative process—the director, designers, dramaturg, all in the room together for everything. It’s an amazing way to work, it’s fun, it’s exciting; the brilliance of six amazingly creative people in the room is stronger than one or two or three, so I really value that way of working and don’t know any other way.

Have people advised you to move to New York?

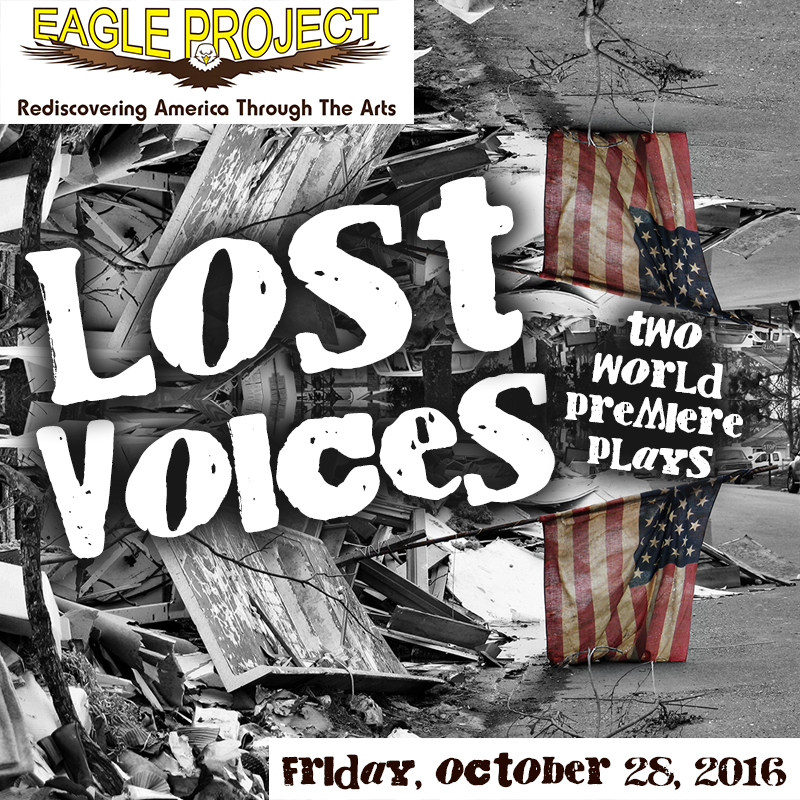

All the time. That’s another thing! Everyone assumes you’re trying to get to New York or you’re trying to get to Broadway. I don’t think about either of those things. There’s nothing wrong with those things, but I don’t sit around thinking about them. I sit around thinking of all the work I have to do and all the commissions I’m behind on. I sit around working in amazing theaters all over the country. [My agent] submits my work to all the theaters in New York, and they’ve rejected nearly everything. Last year was my first small production in New York, a commissioned one-act at the HERE Arts Center with a company called Eagle Project.

How do you think your career might have been different there?

I think it would be very different in the kind of writer I am. I feel fortunate that I got to develop a specific voice that is mine, and that I understand and own. If I’m watching a play, I can say within ten minutes, “Oh, this writer is from New York.” There’s a similarity of training, similarity of style, similarity of whatever is in the water. I can tell a New York City playwright, and that would kind of bum me out if that was me. Being by myself and developing my voice all over the country allows me to focus on what my voice is without the influence of one specific region. I’m being influenced from everywhere.

Is there a voice to the Los Angeles playwright?

I can’t identify a clear playwright voice, but there is a clear LA theater style that’s really lovely. I’ve seen the theater scene merge in the past ten or 15 years, to where I can see an LA play, and know it came out of LA or was produced here because of its style. It’s more about the staging and presentation, but we do have more and more LA-based playwrights who are starting to come into their own. Most are transplants, but we do have some who have grown up here, and have been here before TV became the most popular thing to do.

My husband is from Los Angeles. He’s a sculptor, and has many machines, so he’s not mobile, and he was here with his studio already. We’re very fortunate to have a rent-controlled apartment because we couldn’t afford to live in the rest of LA right now. If we lost our apartment, we would have to leave.

Have you been produced in LA?

It’s pretty rare, but I had one commission produced at Cornerstone Theater Company a year ago, and that was the first in nine years. The only other production was at Native Voices at the Autry when I was first starting out.

URBAN REZ at Cornerstone

Is there resistance to the idea?

I wish I knew. I have no idea. It’s weird. I’m in the Playwrights’ Union, a group of LA Playwrights. I spend a lot of time with LA playwrights and at LA theater. I’m not quite sure why I don’t get produced here.

How do you think #PLONY differ from NYC playwrights?

I work really hard at the business of playwriting. I’ve become an excellent networker. A lot of people think that is going to meet people who can hire me, but that’s not it at all. The theater world is incredibly small. I go find like-minded people who are artistically in the same vein I’m in and may make good collaborators one day. Over time, we may get to work together. It can take years of knowing someone before the right opportunity meets our interest in working together. In that time we are developing a relationship and growing as artists in the same direction.

I almost never ask people to read my work. The last thing people need is more playwrights shoving scripts in their faces. It’s exhausting what they go through, and the amount of abuse they take from playwrights. I’m terrified of being one of those, so I don’t push my scripts. I just get to know people and let them get to know me, because, ultimately, this business we’re in comes down to relationships and wanting to be in the room with someone for weeks. That quality is way up there in a level of importance, along with how good a writer you are. There’s a million amazing writers, but who do you want to spend time with in the room? None of us get paid enough to hang out with someone who’s crabby or pushing.

I also go to conferences, and I’m on the board of directors for Theatre Communications Group, and I’m really careful about that relationship. ADs don’t need another playwright pushing stuff on them. Their jobs are so difficult, so I let them come to me and say, “Hey, you might be someone that might work well with my theater.” Then I send them a script. I’m also very uncomfortable with self-promotion, so I’m much better at getting to know people and finding friends.

What proactive steps do you feel like PLONY can take in furthering their careers?

I’m not in any way a massive social media person, but my Facebook and Instagram are entirely about my work, so people can get to know me as an artist and what I’m about, and not pictures of food and dog and children—well there’s the occasional food and dog and child. I do submit to opportunities, but it gets exhausting, and I have taken years off at a time from submitting to the big programs, and sometimes I don’t submit anything because of how exhausting it gets. But the reality is that it gets your work read by people who have to read your work as opposed to some poor person who has 50 scripts on their desk. And sometimes, I’ll meet someone and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, I was on the panel. I’ve been wanting to meet you,’ and we end up doing something together. My tolerance to submitting is pretty low because it takes so much time and energy and nobody likes getting a million rejection letters.

Would you go back to television now?

My agent is always like, “No pressure, but do you want to go back to TV?” He does submit me for things that he thinks are perfect for me, and I’ve looked at developing a show, but I don’t want to give up my theater career. If it worked out that I could do something in television that I loved and felt passionate about without giving up my theater career, I’d do it. I’m driven by passion, not money. I’ve never had money, so I don’t feel its loss, and it’s not a motivator. My work can do good in the world and change people’s lives, and, if I found a television project that could do all that, I’d do it. My primary goal as a human is to change people’s thinking and the way the world works, and I happen to use theater to do that.

I do writing and theater workshops with indigenous youth all over the country. I always tell them, dialogue is just people talking. If you can talk, you can write dialogue. You don’t need grammar, spelling, fancy equipment. I go to a lot of places where people don’t have Internet or electricity; you don’t need those things to be a playwright. You can do plays in the middle of the prairie, in Alaska on a mountain, anywhere. For some reason, we see playwriting as very mysterious, and it’s the easiest thing. You can do theater exactly where you are. I have this group I work with that has made an amphitheater in the middle of South Dakota on the hillside, and they’re out there writing and performing plays. They’re amazing. I really love that about theater.

—Please follow me on Twitter @donnahoke or like me on Facebook at Donna Hoke, Playwright.

—Playwrights, remember to explore the Real Inspiration For Playwrights Project, a 52-post series of wonderful advice from Literary Managers and Artistic Directors on getting your plays produced. Click RIPP at the upper right.

—To read entries in the popular #PLONY (Playwrights Living Outside New York) series, click here or #PLONY in the category listing at upper right.

—To participate in Trade A Play Tuesday (#TAPT) or Playwrights Offering Free Feedback (#POFF), click.

—To read the #365gratefulplaywright series, click here or the category listing at upper right.

I really enjoyed reading Larissa interview. That’s a great way to start out. I know a man who wrote hot to write a screenplay and got a call from will smith. Larissa story is so inspiring.